| |

| |

Marias Pass This is one pass that was

probably (or maybe) never part of a

planned touring route on a long tour. The

reason is that is is roughly parallel to Logan Pass

(Going to the Sun Road), one of the most

spectacular roads in North America. - That

is until 2020, year of the corona

epidemic. During this August (and other

months too) all entrances on the east side

of Glacier National Park were closed by

the Blackfeet Indian government. It

wouldn't have been the first epidemic,

that came over a pass from the west -more

below. During summer 2020 connecting to

the eastern approach of Logan Pass was

impossible, or at least impractical. At

the same time traffic on Marias Pass was

much lighter. I had a chance before to

ride this pass and passed it up, because

of too much traffic. This time that was

not a problem. Still - this is not the

most bike friendly road in America, but

really pretty good, considering this is

Montana.

In the huge summit parking lot

are two monuments, one dedicated to

Roosevelt and his public land policies, the

other one to "Stevens the Second", who is

described further in the history section

below. The consensus seems to be that the

exploring Stevens in his stocking cap makes

a much more handsome monument, than the

abstract obelisk, dedicated to Theodore

Roosevelt. In any case - they are definitely

located too close to one another, and the

style and contents of the two very different

monuments clash. But then - for a parking

lot it's pretty good.

From

West. (also described upwards). Much

of this side has no shoulder. The beginning

from West Glacier and the approaching the

top, there is a narrow shoulder with limited

usefulness. In order to get at least 500ft

of elevation gain, I had to go search for it

it on Mt49 north of West Glacier. Continuing

on US2 towards Browning the road stays level

or climbs slightly for at least several

miles. The best thing about this side

is, there is an open constant great view of

the peaks to the north until you reach the

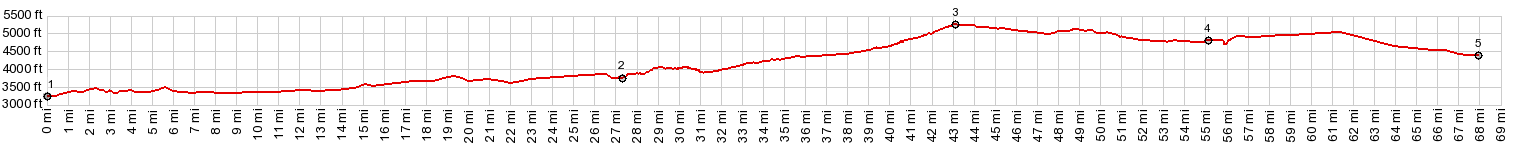

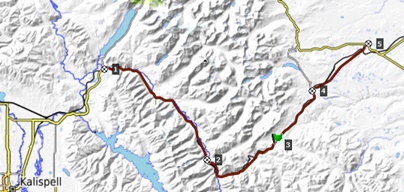

Continental Divide Dayride with this point as highest summit: ( <FR595 Lolo Pass - Granite Pass s(u) | MacDonald Pass > ) Marias Pass x2 : US2 near Flathead River access, Walton Ranger Station <> US2 west <> Marias Pass <> West Glacier <> a few miles of separate out and backs on US2 towards Browning and Mt49 north : 66.1miles with 3410ft of climbing in 5:43hrs (garmin etrex30 r5:20.7.6). History It does not seem, that Marias Pass would be difficult to find, even without a major highway going through it. It is a major demarcation between Canadian type Rockies (even though they are still in the US) to the north and the straight ridgeline "basin and range" type Rockies to the south. And it is true that its location, or at least existence has been known, since the earliest pass history in America. But finding it and using this knowledge has been a major problem, that probably altered history. Marias Pass is the lowest Continental Divide Crossing in the US. But it is not the easiest. Just think of New Mexico where the CD often runs along a shallow breadloaf on a high plain. Instead the impetus to explore it and use it, came from economic reasons and from north of the border. Within a couple of years after Lewis and Clarke, David Thompson had been crossing the Continental Divde at Howse Pass (which is a trail today, accessible from the Icefields Parkway) from the east in Canada and then float down it into today's Montana, in order to track and trade trinkets for furs. He approached this area from Coeur d'Alene region, ie the west. National boundaries and the control of the two competing fur companies (Thompson's North-West company, and the American Hudson's Bay company) were not yet defined at this time of initial exploration. Howse Pass had suited Thompson just fine up to this point. But Indian problems, that had their root in the initial conflicts with Lewis and Clarke (mentioned above) made it seem to Thompson, that Howse Pass had become a very troublesome route. And so in 1810, Thompson, accompanied by Flathead guides explored up the middle fork of the Flathead River. All were armed with rifles. At the top of the pass they were ambushed by Blackfeet, armed with bows and arrows. The guns won the battle, but lost any prospect for the peaceful use of trading and tracking by any fur companies for the rest of time. Thompson instead scouted for high passes in the Canadian Rockies, and reached such out-of-the-way mountaineering goals as Athabasca Pass, instead of this throughfare that would one day contain a major highway. The Stevens Survey. From now on the location of this pass was general knowledge for those people that had a economic or national interest in it. But finding it would be a problem, much of it because of its initial hostile Blackfeet - Whites relationship. The next person tasked to find it, by all accounts, didn't actually try to find it very hard. It is now many years later, 1853. But Montana, part of Washington territory, remains a wilderness, except for an enclave around St Mary's Mission which father DeSmet built at the eastern base of Lolo Pass in 1841. But this is about to change with the governor of Washington territory, Isaac Ingalls Stevens, about to unleash his Stevens Survey, in order to help progress in economic prosperity and maybe a transcontinental railroad across Montana. The person tasked with exploring the pass, was his chief engineer and his former fellow student at Andover, Frederick W. Lander. Lander would later pioneer the Lander cutoff of the Oregon trail. But apparently at this time the relationship was hampered by army routines such as 4am breakfasts, and other army dutys, such as prescribed trout catching and showers. When Lander and his handfull of men returned from their mission, they had crossed Lews and Clarke Pass, and pioneered a mountaineering route in the Sapphire Range - anything but exploring Marias Pass. The Railroads. From now on, finding Marias Pass again, would be up to railroad people themselves. After all they had the most to gain from it too. The relationship with the Indians on the east side of the pass had not improved, probably even worsened, because of an imported small pox epidemic. Finally Stevens asked his old friend, W A Tinkham, a civil engineer for the railroad to take a look at the pass. In October 1853, Tinkham was ready to approach the area from the west, having crossed the Continental Divide first from the east over Cadotte Pass (an old historic trail west of Helena, parallel to today's Mac Donald Pass). Tinkham was not scared of Blackfeet, but apparently no trail blazer. He came back describing a mountain pass 7600ft high - more than 2000ft than the real Marias Pass "with a bare rocky ridge ... often just wide enough for the feet of a horse. ... - a great description of a trail to Pitamkan Pass in today's Glacier National Park, but not so fitting for Marias Pass. James Doty was a technichan for the railroad, with Tinkham as a superior. James Doty was a skeptic. During an explorational outing with only three men next May, in order to have a look at British North America, Waterton Lake and other places, he met an Indian who showed him the loation of Marias Pass, and also also the location of the pass 20 miles to the north where he claimed Tinkham crossed. But - convincing a superior in a company structure of his errors may not always be the wisest thing to do, and so Doty the technician, kept quiet, and missed having a major landmark named after him, like Tinkham. And so the Stevens Pacific survey of 1853 ended with the Marias Pass matter unresolved. The survey managed to put the previousely unreported Nez Perce Pass on the map, and explored Lewis and Clarke's Lolo Pass. But the Marias Pass matter would have to wait till the other side of the Civil War years. After 1870 the Canadian James Gerome Hill found himself as owner of a number of rairoads in the north central part of North America. From the east these roads reached Butte. But Hill wanted to connect the rails to Puget Sound, and he wanted to call them the Great Northern Railroad. Now it was Hill's turn to order people around to find him a route. The first was the major stake holder in the railroad, a certain Major Rogers. He favored what is now Roger's Pass. When it came to Marias Pass his contact person died and Rogers turned in an "incomplete", much like Lander did to Stevens. And again it is a case of "file and rank to the rescue". The chain of command was looking for somebody to do the job. The process drilled downwards, and included threatening to rescind a promotion of chief engineer E F Beckler, further down to John F Stevens, no relation to the govenor of Washington territory. This Stevens was a first class axman, and instrument handler without engineer training, who had worked before on the Rio Grande Railway over Tennesee Pass and Fremont Pass. The new Stevens approached the area from the east through hostile Blackfeet territory. His outfit was limited to a wagon, a mule and horse, snowshoes and other minor things. He had an assistant but he reportetly was not of much help because of a whiskey problem. Blackfeet guides refused to work for him, because of continued "bad spiriit activity". But an outcast Flathead guide finally lead him as far as the location known as "False Summit" on a cold December 11, 1889. The spot acquired its name later because a team of railroad surveyors mistakenly identified it as the Continental Divide Crossing and the real summit. The spot is marked on many maps today. From there Stevens reportedly surveyed the pass alone in deep snow and freezing conditions. Stevens was not only promoted to Chief Engineer in 1893. Long after HIll's death the railroad commissioned a scupture of the intrepid explorer for the top of the pass. It can still be admired today, and railroad management has left no stone unturned, to capitalize on this heroic story of mismanagement. Modern Highways. The 57 miles of road over the pass were inspired in 1917 by the new Glacier National Park. Enter the Flathead Motorclub into history, exit the Flathead Indian guides. They convinced the rest of the world, that the park needed road access from the east. The road opened on July 19,1930. Only three years later, a more spectacular motoring road opened parallel to old Marias Pass: Going to the Sun Road over Logan Pass. |

|

|

advertisement |

|

|

advertisement |